The need for Britain to secure its energy future, wean off foreign energy in uncertain times and achieve our Net Zero 2050 objectives is well documented.

Is nuclear energy the one stone to kill these 3 birds?

In 2019 the then-UK Government pledged (and legislated) to improve on previous promises, committing to Net-Zero emissions by 2050 through the Climate Change Act.

As divisive as the climate change debate was at the time - natural fluctuations or man-made? - beyond the environmental considerations, everyone agrees now that actions need to be taken when gas prices start to triple mid-winter.

With the UK’s nuclear energy output shrinking since 1998, the time to act is now to replace the lost capacity. As aging stations close and are decommissioned, we need and have begun to pursue a different tack.

Five of our six existing plants will be offline within the decade, and we currently have only one new project in construction with further approval. By comparison, France currently has nine times more nuclear capacity than the UK. France is the world's largest net exporter of electricity and gains over €3 billion per year from this.

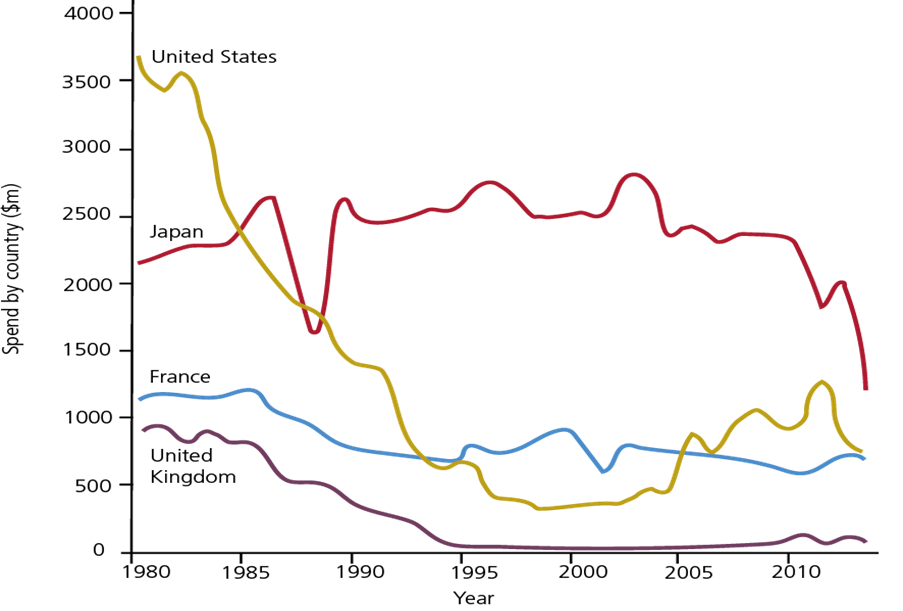

Figure 1- House of Lords. Demonstrates dwindling investment in British nuclear from 1980 to 2015

The Three-Wave Strategy

Over the next 30 years to achieve our net output objectives from nuclear it is vital that there are:

- Pressurised Water Reactors (PWR) such as HPC / SZC

- Small Modular Reactors – deployable within the next 8 – 10 years

- Advanced Modular Reactors – ambitions for a pilot plant in the next 10 years

The current generation of PWR / Light Water Reactors (LWR) are large, highly complex engineering projects with lengthy, expensive builds. The duration of the builds naturally adds to the cost of the electricity produced. A reduction in the size of these PWR / LWRs facilitates easier assembly on site and means that reactor modules can be factory built – vastly reducing both build and electricity costs.

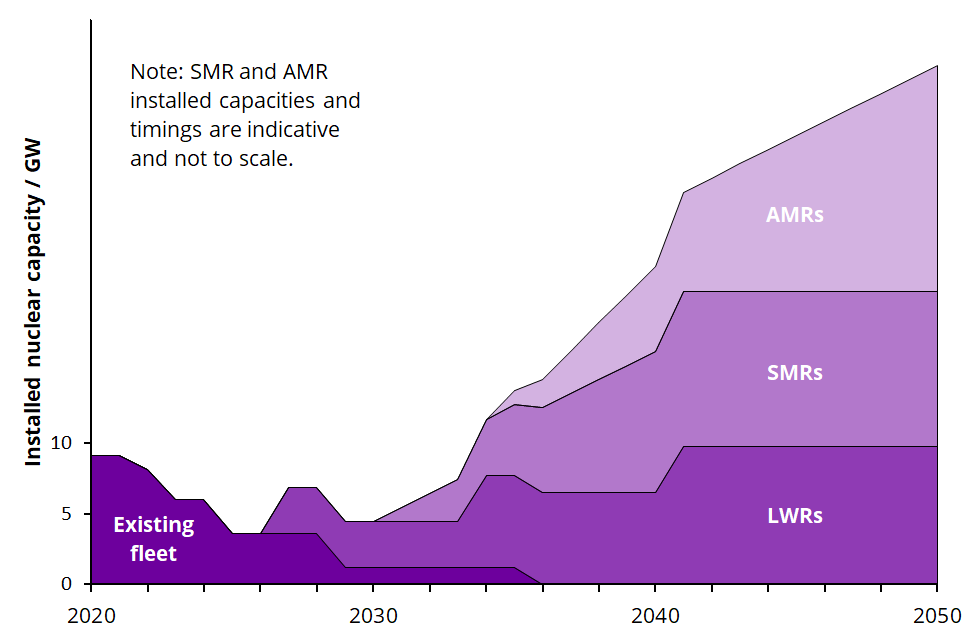

Figure 2- demonstrates the decline of the existing UK nuclear fleet, and how the three-wave strategy can supplement our energy output.

Figure 2- adapted from NIRAB, assuming successful completion of HPC and SZC LWRs

Where can these plants go?

There are 8 sites in the UK potentially suitable for new nuclear plants (Bradwell, Hartlepool, Heysham, Hinkley Point, Oldbury, Sizewell, Sellafield and Wylfa), any successful future plans are predicated on local acceptance of new nuclear– a much more Influential factor than when Britain’s last nuclear power plant was commissioned in 1988.

In 2022, then Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that “to facilitate our ambitious deployment plans we will also develop an overall siting strategy for the long term”.

The need for new sites, and in turn, local approval, means that a charm offensive is required to amass community support. Latent issues such as adverse environmental impact, adverse effects on local wildlife, and the perceived eyesore that decommissioned plants represent are barriers that will have to be contended with. Lessons can be learned from the fairly successful consent–based approach to finding a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF).

So what happens now?

A paper released by the Dalton Nuclear Institute has made a series of recommendations for the Government and industry. Chief among these is to develop an integrated framework for the delivery of nuclear energy in the UK. A solid understanding of the full lifecycle of the future nuclear provision will be essential to ensure that a suitable nuclear sector can be delivered by 2050.